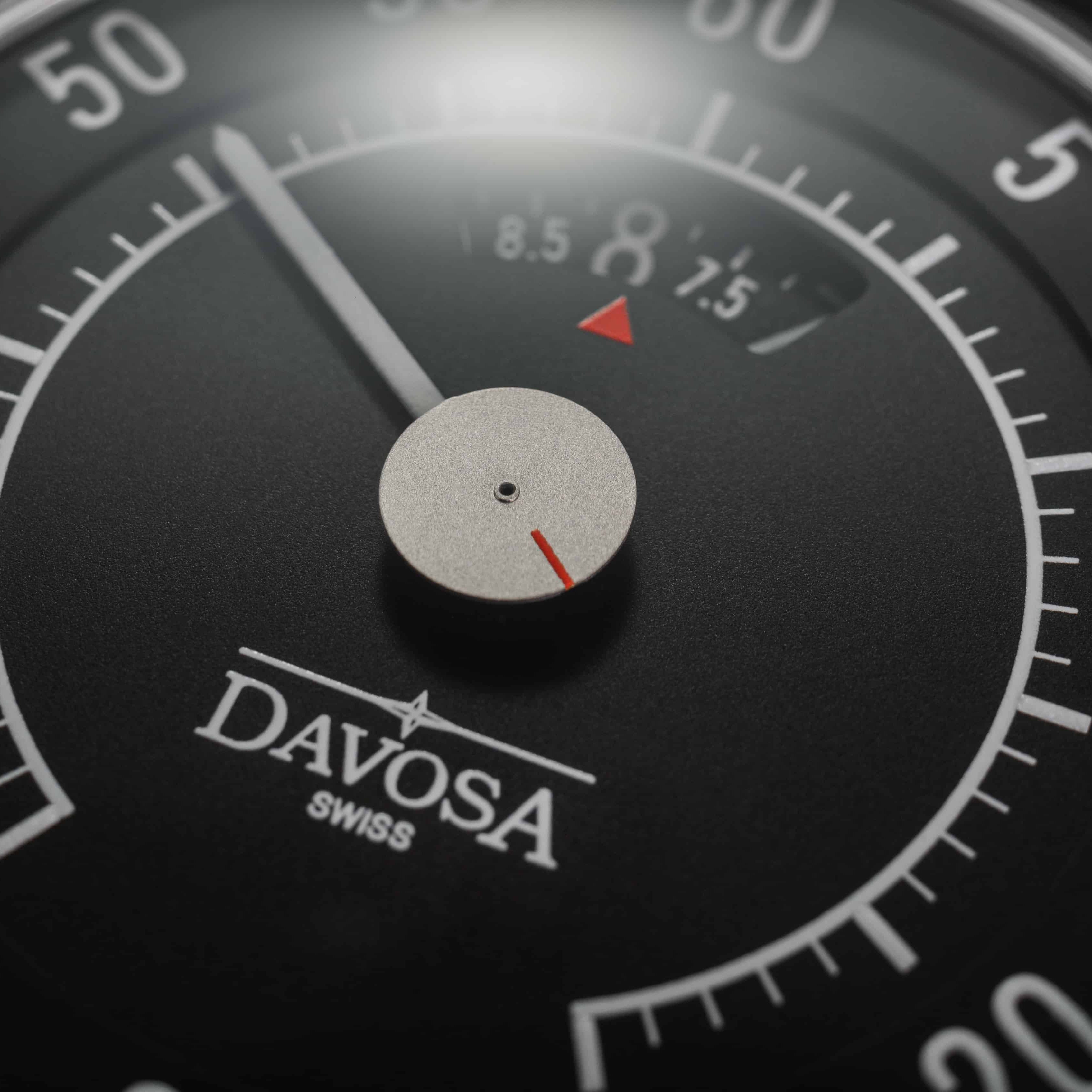

How many times have we horology lovers looked at an advertisement for a watch in a magazine or website? We have often found ourselves appreciating the lines, design, and overall style, perhaps in the details of the photos.

And looking at these ads more carefully, we realize that the hands of the watches are invariably placed in a very precise position: ten past ten. So, where does this curious habit come from? Let's find out together, learning that clocks represent much more than a simple timepiece, even in this case, but they enter the depths of our psyche!

Facts about 10:10

Before we determine why timepieces are traditionally represented showing this time, we should ask ourselves some questions, which will tell us a lot about our relationship with timepieces. And this goes back to the terminology we use to refer to the clock elements.

First, let's pay attention to the name we use to refer to the watch main indicator: the hands. We name them after the most fundamental appendages of our bodies. And do you know why? Because they indicate time. Indicating time happened before clocks were born, as there was already something that marked time: sundials gnomon - which have been used since the time of the Egyptians - with their gnomons. During the course of the day, the sun would project the gnomon's shadow on a field divided in sectors, showing the time.

Examining this scale, what we now call a dial, we realize that modern clocks have placed noon in an exact position: at the top. It is right at the highest point that the sun reaches in the sky during its daily path. An analogy that is not at all surprising but which leads us to consider our clocks as a representation of the universe around them. And what we now call hands should actually be called fingers: because they once indicated the sun's position in the sky.

Returning to the sundials and their gnomon, the analogy of this giant finger indicating the hours was then taken up in "modern" clocks to show the hours on the dial, which was also called, not so curiously, "face." So, when we wear our watches upside down - or better, inside out, we are hiding their face.

So, we have two anthropomorphic elements in the clock - the face and the hands. Are we still missing something? The answer is yes: we are forgetting how these elements combine, especially in our imagination, thanks to a mental process called pareidolia.

Pareidolia - a name that comes to us from the Greek and means "wrong image" - is that mental process that leads us to look for assonances between objects of different types. So, for example, we see features of known things in the shape of clouds: when we say that a cloud we are looking at looks like a cat, we are setting a process of pareidolia. And this also happens with our timepieces, where on the "face" of the watch, we see a face, and the hands, which mark the hours, represent its mouth.

Why are all clocks set to 10:10?

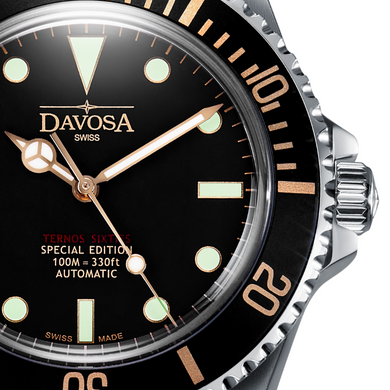

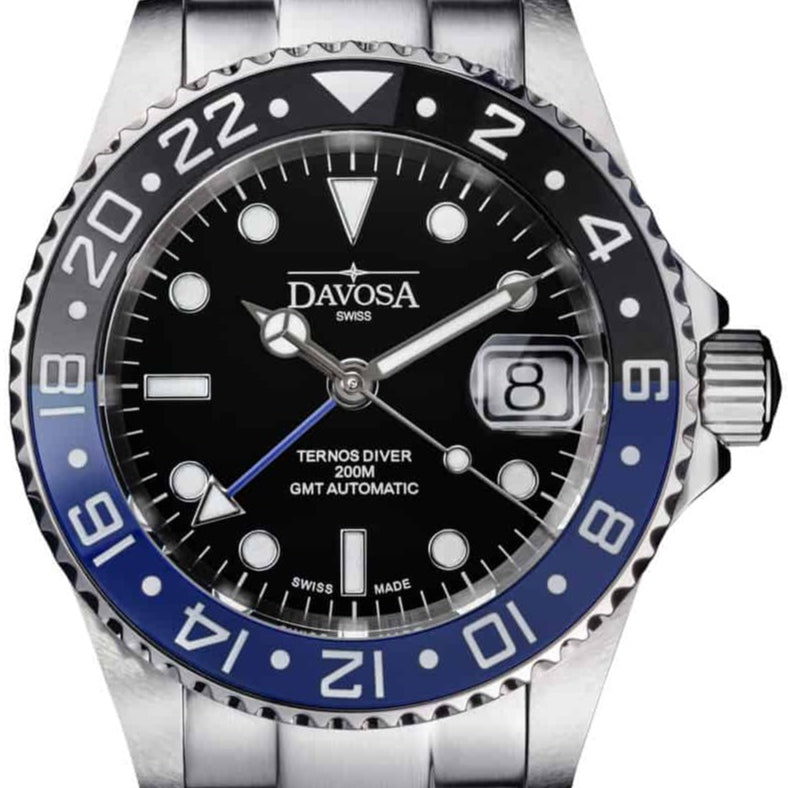

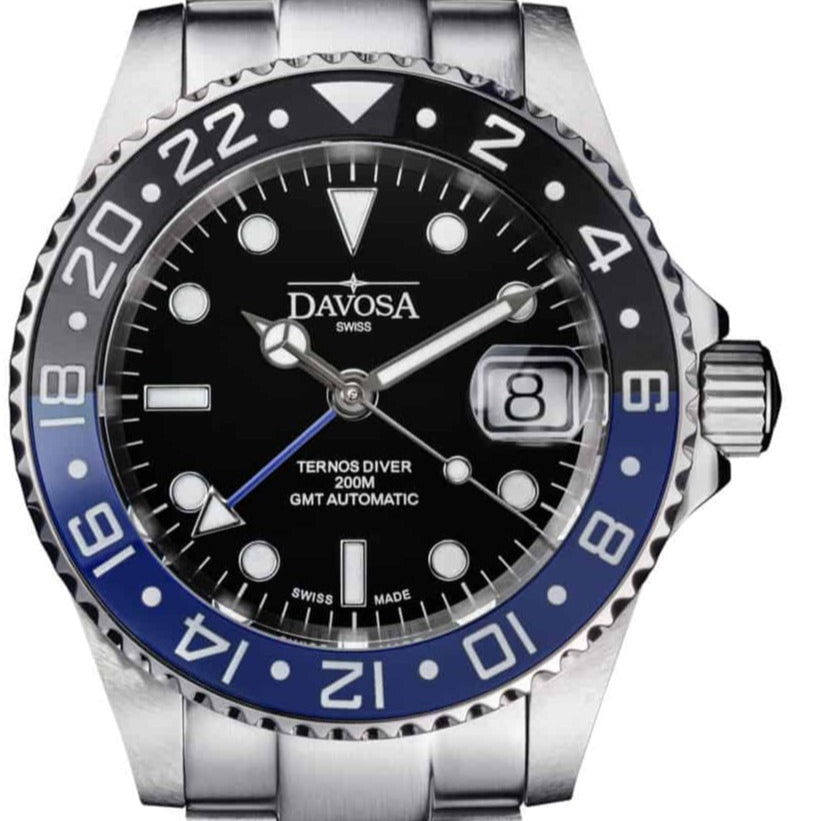

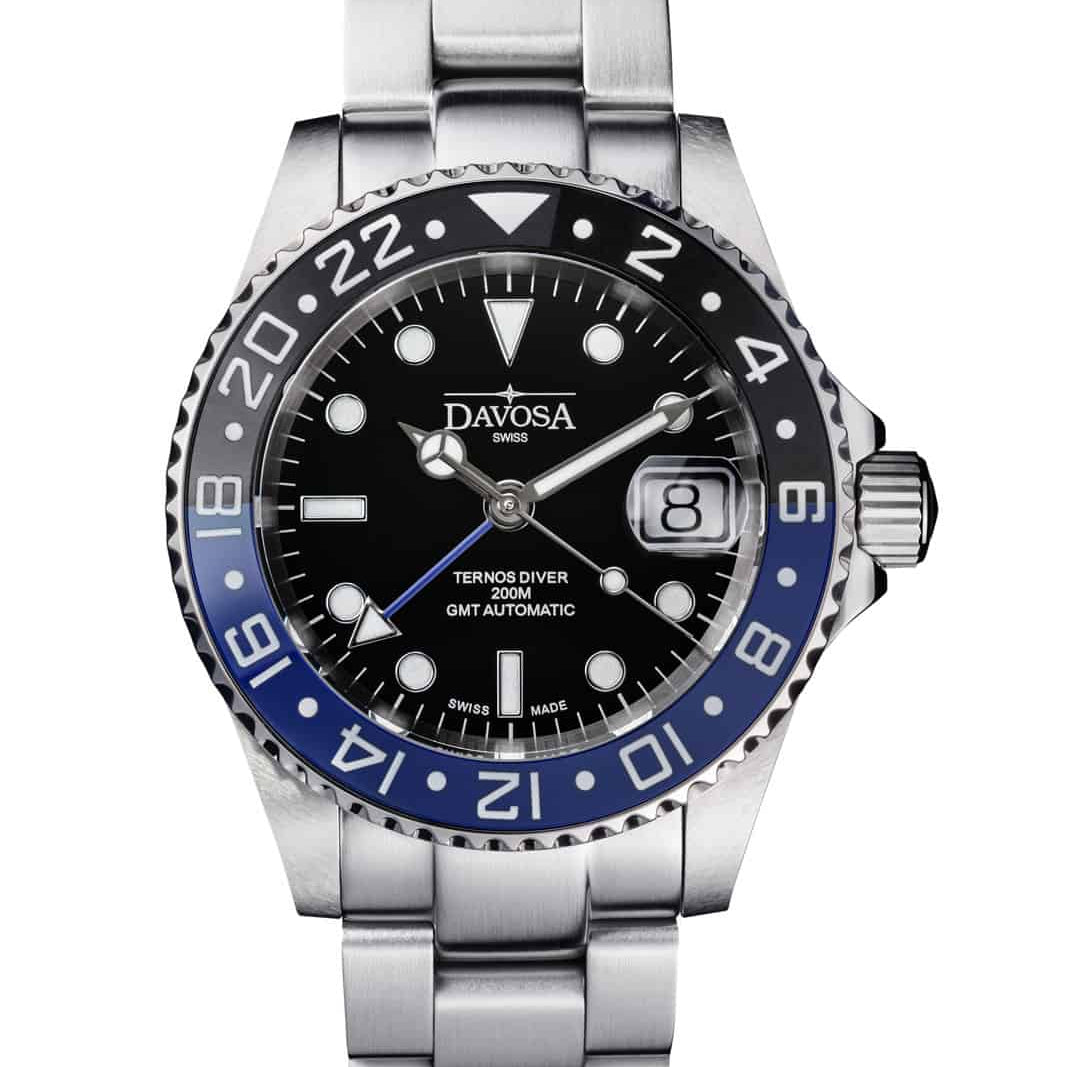

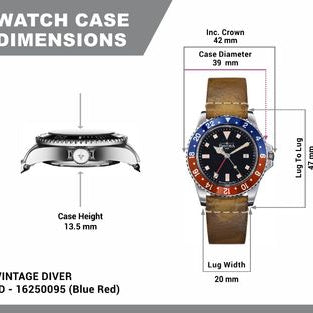

Let's get to the heart of our problem - or rather, its solution. The hands arranged in this way represent a smiling face and give us an attractive and pleasant image. Let's try moving the hands back to a position like 9:15. We will immediately see that the smile flattens and thus, fades. The face of the clock is no longer sympathetic; it looks at us with indifference. And if we continue further, putting the hands-on eight twenty, the unconcern of the clock's mouth becomes sadness.

On the contrary, if we try to tighten our smile, putting the hands at eleven five, the smile becomes a sneer. And what's more, the hands would hide the manufacturer's name, which is usually placed right there, at twelve o'clock, centered, in the place where our eyes rest first (that's why Maisons typically put their logo right there).

Incidentally, try looking at your computer screen: where do your eyes rest? Right there: at about 2/3 of the height of the screen (a position that is very close to the proportion indicated by the famous "golden section"), and at its center. In watches, the same thing happens - and what the manufacturers are interested in is to let people know that they produced that watch.

Have you noticed that we are always talking about bilateral symmetry, i.e., hands that are specularly balanced at the two ends of the dial? This is also where pareidolia kicks in. A person's face is specular, or at least reasonably specular. If it is not, there is something strange, and "strange" is not a good adjective to suggest to your audience when advertising your products.

Then let's remember that there are always other reasons in the field: but in general, these elements come into play when we look at an image of a timepiece, and these little touches make it more "appealing" and captivating.

10:10 time history

The history of the two hands, for hours and minutes, was a late discovery in watchmaking. The first clocks were not precise enough to have two hands, so it was only relatively late that our ancestors began to evaluate watches according to the criteria of pareidolia: we are talking about the late seventeenth century. However, we can't know for sure if, even in the past, there was this particular type of relationship with clocks.

In fact, in the only documents that describe them and that we can still see, namely the portraits, we realize that the painters of the time were not influenced by this phenomenon and portrayed their subjects by inserting clocks that showed every variety of time on the dial, so this "transference" began in much more recent times, that is, since the watches have not started to be shown to the public in advertising. Fortunately, in this case we have an extensive sampling of examples to draw on.

We know for sure that the first advertisements for watches are very old: Abraham Louis Breguet himself had promoted his "Souscription" through a printed brochure. But it was only towards the end of the nineteenth century that we had the first watches portrayed on advertisements, usually reproduced by drawing.

Examining the old advertisements of watch companies, we can see that the positions used to set the hands are the most diverse and started to converge towards the fateful "ten and ten" around the seventies. However, one common feature is evident: in all advertisements, important details of the watch are not hidden by the hands.

Main Takeaways

As you can see, there is a complex process behind a detail that appears at first glance absolutely banal, such as placing hands at a specific time when taking photographs of a timepiece. Even this tells us a lot about the care manufacturers take to put their products in the best light.

And this, in part, reassures us that when we buy a timepiece, our money is being spent on a product designed, engineered, even in its minutest details, and marketed by professionals.

The Davosa-USA.com website is NOT affiliated in any way with Audemars Piguet, Franck Muller USA, Inc. Richard Mille or Richemont Companies, Seiko, or any other brand which is not Davosa Swiss. Rolex is a registered trademark of Rolex USA. Davosa-USA website is not an authorized dealer, reseller, or distributor for Rolex and is in NO WAY affiliated with Rolex SA or Rolex USA or any other brand besides Davosa Swiss. |